A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves

By JASON DePARLE New York Times

Published: April 22, 2007

On June 25, 1980 (a date he would remember), a good-natured Filipino pool-maintenance man gathered his wife and five children for an upsetting ride to the Manila airport. At 36, Emmet Comodas had lived a hard life without growing hardened, which was a mixed blessing given the indignities of his poverty. Orphaned at 8, raised on the Manila streets where he hawked cigarettes, he had hustled a job at a government sports complex and held it for nearly two decades. On the spectrum of Filipino poverty, that alone marked him as a man of modest fortune. But a monthly salary of $50 did not keep his family fed.

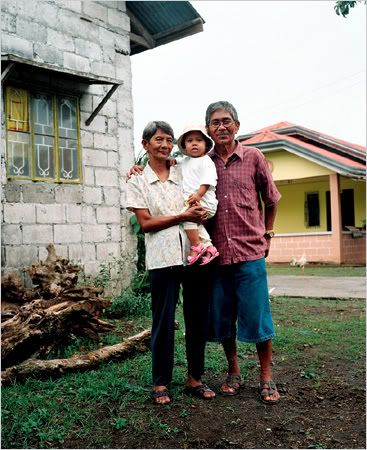

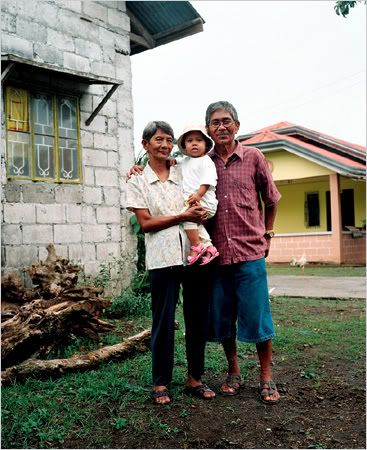

Stephanie Sinclair for The New York Times

The Comodases with their granddaughter Precious Lara.

Stephanie Sinclair for The New York Times

Red-Carpet Treatment O.F.W.’s, or Overseas Filipino Workers, are often treated like heroes upon their return to Manila because of all the money they send home.;

Stephanie Sinclair for The New York Times

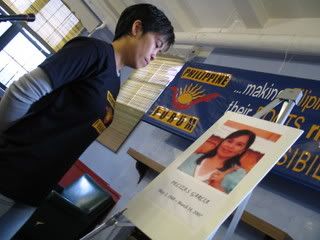

Christmas Bonus Globe Telecom is just one of many Filipino companies that award prizes to overseas Filipino workers and their families.

Stephanie Sinclair for The New York Times

The Next Generation? Precious Lara Villanueva with her grandmother Tita Comodas, who is raising Precious Lara while her mother, Rosalie, works abroad. Tita’s husband, Emmet Comodas, was an overseas worker for two decades.

Home was a one-room, scrap-wood shanty in a warren of alleys and stinking canals, hidden by the whitewashed walls of an Imelda Marcos beautification campaign. He had borrowed money at usurious rates to start a tiny store, which a thief had plundered. His greatest fears centered on his 11-year-old daughter, Rowena, who had a congenital heart defect that turned her lips blue and fingernails black and who needed care he could not afford. After years of worrying over her frail physique, Emmet dropped to his moldering floor and asked God for a decision: take her or let him have her.

God answered in a mysterious way. Not long after, Emmet’s boss offered him a pool-cleaning job in Saudi Arabia. Emmet would make 10 times as much as he made in Manila. He would also live 4,500 miles from his family in an Islamic autocracy where stories of abused laborers were rife. He accepted on the spot. His wife, Tita, was afraid of the slum where she soon would be raising children alone, and she knew that overseas workers often had affairs. She also knew their kids ate better because of the money the workers sent home. She spent her last few pesos for admission to an airport lounge where she could wave at the vanishing jet, then went home to cry and wait.

Two years later, on Aug. 2, 1982 (another date he would remember), Emmet walked off the returning flight with chocolate for the kids, earrings for Tita and a bag of duty-free cigarettes, his loneliness abroad having made him a chain smoker. His 2-year-old son, Boyet, considered him a stranger and cried at his touch, though as Emmet later said, “I was too happy to be sad.” He gave himself a party, replaced the shanty’s rotted walls and put on a new roof. Then after three months at home, he left for Saudi Arabia again. And again. And again and again: by the time Emmet ended the cycle and came home for good, he had been gone for nearly two decades. Boyet was grown.

Deprived of their father while sustained by his wages, the Comodas children spent their early lives studying Emmet’s example. Now they have copied it. All five of them, including Rowena, grew up to become overseas workers. Four are still working abroad. And the middle child, Rosalie — a nurse in Abu Dhabi — faces a parallel to her father’s life that she finds all too exact. She has an 18-month-old back in the Philippines who views her as a stranger and resists her touch. What started as Emmet’s act of desperation has become his children’s way of life: leaving in order to live.

About 200 million migrants from different countries are scattered across the globe, supporting a population back home that is as big if not bigger. Were these half-billion or so people to constitute a state — migration nation — it would rank as the world’s third-largest. While some migrants go abroad with Ph.D.’s, most travel as Emmet did, with modest skills but fearsome motivation. The risks migrants face are widely known, including the risk of death, but the amounts they secure for their families have just recently come into view. Migrants worldwide sent home an estimated $300 billion last year — nearly three times the world’s foreign-aid budgets combined. These sums — “remittances” — bring Morocco more money than tourism does. They bring Sri Lanka more money than tea does.

The numbers, which have doubled in the past five years, have riveted the attention of development experts who once paid them little mind. One study after another has examined how private money, in the form of remittances, might serve the public good. A growing number of economists see migrants, and the money they send home, as a part of the solution to global poverty.

Yet competing with the literature of gain is a parallel literature of loss. About half the world’s migrants are women, many of whom care for children abroad while leaving their own children home. “Your loved ones across that ocean . . . ,” Nadine Sarreal, a Filipina poet in Singapore, warns:

Will sit at breakfast and try not to gaze

Where you would sit at the table.

Meals now divided by five

Instead of six, don’t feed an emptiness.

Earlier waves of globalization, the movement of money and goods, were shaped by mediating institutions and protocols. The International Monetary Fund regulates finance. The World Trade Organization regularizes trade. The movement of people — the most intimate form of globalization — is the one with the fewest rules. There is no “World Migration Organization” to monitor the migrants’ fate. A Kurd gaining asylum in Sweden can have his children taught school in their mother tongue, while a Filipino bringing a Bible into Riyadh risks being expelled.

The growth in migration has roiled the West, but demographic logic suggests it will only continue. Aging industrial economies need workers. People in poor countries need jobs. Transportation and communication have made moving easier. And the potential economic gains are at record highs. A Central American laborer who moves to the United States can expect to multiply his earnings about six times after adjusting for the higher cost of living. That is a pay raise about twice as large as the one that propelled the last great wave of immigration a century ago.

With about one Filipino worker in seven abroad at any given time, migration is to the Philippines what cars once were to Detroit: its civil religion. A million Overseas Filipino Workers — O.F.W.’s — left last year, enough to fill six 747s a day. Nearly half the country’s 10-to-12-year-olds say they have thought about whether to go. Television novellas plumb the migrants’ loneliness. Politicians court their votes. Real estate salesmen bury them in condominium brochures. Drive by the Central Bank during the holiday season, and you will find a high-rise graph of the year’s remittances strung up in Christmas lights.

Across the archipelago, stories of rags to riches compete with stories of rags to rags. New malls define the landscape; so do left-behind kids. Gain and loss are so thoroughly joined that the logo of the migrant welfare agency shows the sun doing battle with the rain. Local idiom stresses the uncertainty of the migrant’s lot. An O.F.W. does not say he is off to make his fortune. He says, “I am going to try my luck.”

A kilometer of crimson stretched across the Manila airport, awaiting a planeload of returning workers and the president who would greet them. The V.I.P. lounge hummed with marketing schemes aimed at migrants and their families. Globe Telecom had got its name on the security guards’ vests. A Microsoft rep had flown in from the States with a prototype of an Internet phone. An executive from Philam Insurance noted that overseas workers buy one of every five new policies. Sirens disrupted the finger food, and a motorcade delivered the diminutive head of state, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who once a year offers rice cakes and red carpet to those she calls “modern heroes.”

Bleary from the eight-hour flight, a few hundred workers from Abu Dhabi swapped puzzled looks for presidential handshakes on their way to baggage claim. Roderick de Guzman, a young car porter, took home the day’s grand prize, a “livelihood package” that included a jeepney, life insurance, $1,000 and a karaoke machine. Too dazed to smile, he held an oversize sweepstakes check while the prize’s sponsors and the president beamed at his side and a squad of news photographers fired away. When it comes to O.F.W.’s, politics and business speak with one voice. Message: We Care.

On the way to the photo op, I squeezed into an elevator beside Arroyo. A president and daughter of a president, she is a seasoned pol who attended Georgetown University (Bill Clinton was a classmate) and has a Ph.D. in economics. I asked why she called migrant workers “heroes” and gathered from her impatient look that it was all she could do to keep from saying “du-uh.”

“They send home more than a billion dollars a month,” she said.

“O.F.W.’s get V.I.P. Treatment, Treats,” reported the next day’s Philippine Daily Inquirer, which runs nearly 600 O.F.W. articles a year. Half have the fevered tone of a gold-rush ad. Half sound like human rights complaints.

“Deployment of O.F.W.’s Hits 1-M Mark.”

“Remittances Seen to Set New Record.”

“Happy Days Here Again for Real Estate Sector.”

“5 Dead O.F.W.’s in Saudi.”

“O.F.W. 18th Pinay Rape Victim in Kuwait.”

“We Slept With Dog, Ate Leftovers for $200/month.”

Nearly 10 percent of the country’s 89 million people live abroad. About 3.6 million are O.F.W.’s — contract workers. Another 3.2 million have migrated permanently, largely to the United States — and 1.3 million more are thought to be overseas illegally. (American visas, which are probably the hardest to get, are also the most coveted, both for the prosperity they promise and because the Philippines, a former colony, retains an unrequited fascination with the U.S.) There are a million O.F.W.’s in Saudi Arabia alone, followed by Japan, Hong Kong, the United Arab Emirates and Taiwan. Yet with workers in at least 170 countries, the O.F.W.’s are literally everywhere, including the high seas. About a quarter of the world’s seafarers come from the Philippines. The Greek word for maid is Filipineza. The “modern heroes” send home $15 billion a year, a seventh of the country’s gross domestic product. Addressing a Manila audience, Rick Warren, the evangelist, called Filipino guest workers the Josephs of their day — toiling in the homes of modern Pharaohs to liberate their people.

For the sheer visuals of the O.F.W. boom, consider Pulong Anahao, a village two hours south of Manila that has been sending Filipinezas to Italy for 30 years. Cement block is the regional style, but these streets boast — the only verb that will do — faux Italianate villas. For the social complexity, turn on “Dahil sa Iyong Paglisan” (“Because You Left”), a Tagalog telenovela. Each show explores a familiar type. “Dodgie,” a driver in Dubai, is livid at his wife’s profligacy. “Dennis” gets fleeced by crooked recruiters on his way to Singapore. “Carlos,” with a wife in Riyadh, is a hapless househusband; he cannot cook or wash, and his son is left out in the rain.

Manila Hospital was aflutter one morning with the taping of the episode about “Wally.” A seafarer home from Greece, he demanded to know where his money had gone, only to discover that his pregnant wife had spent it on antiviral medication. His port-of-call promiscuity had given her H.I.V.

“Qui-et!” the director bellowed, with Wally about to learn of his own infection. It took the actor five takes to summon a sufficiently chilling mix of fear and remorse. A giggly nursing student, fresh from a cameo, paused to chat. She was getting a degree to — what else? — “go abroad and try my luck.”

While the Philippines has exported labor for at least 100 years, the modern system took shape three decades ago under Ferdinand Marcos. Clinging to power through martial law, he faced soaring unemployment, a Communist insurgency and growing urban unrest. Exporting idle Filipinos promised a safety valve and a source of foreign exchange. With a 1974 decree (“to facilitate and regulate the movement of workers in conformity with the national interest”), Marcos sent technocrats circling the globe in search of labor contracts. Annual deployments rose more than tenfold in a decade, to 360,000.

The “People Power” revolution of 1986 replaced him with Corazon Aquino, who as the widow of his slain rival was a figure as un-Marcosian as they come. But the surge in labor migration continued. By the end of her six-year term, annual deployments had nearly doubled. There is no anti-migration camp in Filipino politics. The labor secretary, Arturo Brion, greeted me by saying that he, too, had been an O.F.W., having worked as a lawyer for seven years in Canada. When I asked how a nationalist candidate might fare with a vow to keep workers home, he looked confused. “Nobody would vote for him,” he said.

The political issue is not migration but migrant safety. The formative moment in O.F.W. history, its Alamo, was the 1995 hanging of Flor Contemplacion, a Filipina maid in Singapore. Though she confessed to killing another Filipina maid and a Singaporean child, she did so in an uncertain mental state with weak legal representation; an 11th-hour witness fingered someone else. President Fidel Ramos’s calls for mercy failed, and the martyred maid’s coffin received a hero’s welcome at home. Congressional elections followed, and the new Legislature passed what is variously called Republic Act 8042 and “the migrant workers’ Magna Carta.” It pushed the government’s responsibilities beyond migrant deployment to migrant protection.

Woe now to the Filipino pol who appears not to have migrant welfare in mind. After a Filipino truck driver was kidnapped in Iraq in 2004, Arroyo not only banned all contract work there but also withdrew from the American-led military coalition. Even state visits have the tenor of bail runs. The president triumphed in Saudi Arabia last spring when King Adbullah freed more than 400 workers who had been jailed for petty crimes. But the war in Lebanon last summer threw the Arroyo government into a crisis by displacing thousands of Filipina maids. They returned home with harrowing tales of prewar abuse, including beatings and rape, endured in pursuit of salaries that averaged $200 a month. Embarrassed (and seemingly surprised), the government proposed a “Supermaid” program, a short-term training regimen that would lift the maids’ skills and demand a doubling of their wage. Those not cringing at the name fretted that a pay raise would leave the maids displaced by Bangladeshis.

While every country’s migrants face risks, what makes the Philippines unique is a bureaucracy pledged to reduce them. There is no precise analog for the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration — O.W.W.A. — or its savvy director, Marianito Roque, who is one part international rescue worker and one part domestic fixer. A bureaucratic survivor who rose through the ranks, Roque understands the imperative of making the president look good. Christmas offered plenty of opportunity. With legions of workers coming home, Roque staged thank-you fiestas nationwide.

I pictured them as sedate affairs until I arrived at a mall in Cebu City. Five thousand people pressed against police barricades, aiming cellphone cameras at a fluttering pop star who urged them to buy her music and clothes. O.W.W.A. has its own chorale, which offered the workers “Lady Marmalade” — “Voulez-vous coucher avec moi?” — an odd choice in a country saturated with fears of overseas adultery. Roque raffled off a mountain of rice cookers and electric fans, and the crowd responded with game-show shrieks. He caught an early-morning flight the next day and stormed through two more fiestas.

When the last rice cooker had been claimed and the last voulez-vous belted out, I spotted a man grinning mischievously, as if he were in on his own private joke. An attractive woman hung on his arm with what I mistook as reunion bliss. The bliss, she happily explained, was in the pay. The man, Pepito Montero, boasted that he earned $8,000 a month on a Saudi oil rig, and a flicker of doubt must have crossed my face. His smile broadened at the chance to produce his retort — a mass of $100 bills the size of a tennis ball.

Emmet Comodas migrated to Manila before he migrated abroad. His parents, tenant farmers in the province of Leyte, died before he finished grade school, and he was handed off to an aunt in the capital, 600 miles away. She lived in a muddy squatters’ camp called Leveriza. The alleys were ruled by drunks and gangs, but Emmet wore his geniality as a shield and was quick to make friends. Drawn to commerce more than to school, which he left at 16, Emmet spent much of his youth dodging traffic to sell newspapers and cigarettes. When he grew weary of his aunt’s strictures, he slept on a city bridge.

Among his favorite vending sites was a nearby stadium, Rizal Memorial, though without a sales license he had to sneak in early and hide before events. The canteen manager, admiring his pluck, hired him as a cook. With a bounce in his step from his first real job, Emmet was walking home to Leveriza one day when he spotted a woman, beautiful but frail, in an alley ironing clothes. He was afraid to say hello.

Teresita Portagana came from a higher echelon of the Filipino poor. Her father was a farmhand in nearby Cavite province who managed to buy a few acres of coffee trees. Tita was raised on the farm, the oldest of 11 kids in a close-knit family who shared a single thatched hut. She left school after sixth grade to help her mother manage the growing clan, and when she turned 16 her father sent her to work in a Manila glove factory. She would live with an aunt and send home most of her pay.

Her excitement at the prospect of city living vanished when she saw her aunt’s neighborhood. Leveriza was not just crowded and dangerous; it stank. Stagnant estuaries, which doubled as sewage pits, were filled with discarded bundles of waste dubbed “flying saucers.” When her father learned that Tita was drawing looks from Leveriza boys, he hurried to Manila and moved her out. “One relative in Leveriza is enough,” he said. By then Emmet was pressing his case. Tita considered him plain-looking and “poor as a rat,” but his persistence carried the day. They married on the farm and moved back to Leveriza, where Emmet would be close to work. He was 23, and she had just turned 21.

Similar slums were spreading across the developing world, greeting provincial migrants with welcome mats of squalor. How people survived, and at what cost, was a mystery and a concern. As Tita and Emmet were settling in, F. Landa Jocano, an anthropologist trained at the University of Chicago, moved nearby in search of answers, which eventually formed a noted book, “Slum as a Way of Life.” The setting of his Leveriza-like camp was predictably grim — “wet and muddy,” with a “nauseating smell” and “cardboard hovels” holding six to nine people to the room. But what really stood out were the social conflicts. Despite the Filipinos’ reputation for prizing social accord, husbands beat wives, gangs murdered gangs and tsismis — gossip — was a constant preoccupation. “Envy, jealousy, hatred and other forms of ridicule” coursed through the alleys, and it took a special deftness to thrive. Tita, lacking it, withdrew into herself. “I was talkless,” she said.

Tita and Emmet had three children in four years, and two more later. Their second child. Rowena, was born seven weeks early with a heart defect that went undiagnosed for years. All they knew was that she was constantly sick. The family lived in rented shanties until Emmet won $90 on a horse race and bought a shanty of his own. It was so bug-infested that he burned the walls and rebuilt with secondhand wood. He moved to a pool-cleaning job at the stadium and sold cigarettes on the side.

Still, the holes in the roof meant the children got wet on rainy nights. When she lacked money for vegetables or fish, Tita served the children rice, and when she lacked enough rice for three meals, she served two. A Sikh they called the “boom-bay” lent money at the standard interest rate, 20 percent per month. Emmet borrowed about $130 to open a tiny grocery store, which he planned to run as a sideline with Tita’s help. The thief who robbed it during Holy Week seemed to know that they were busy with a marathon reading of the “Pasyon,” a 24-hour life of Christ. A few months later, Tita became pregnant with their fifth child.

By then the Marcos labor decree was five years old, and the machinery was humming. Saudi Arabia was modernizing overnight. It needed roads, schools, apartments, hospitals and laborers to build them. Filipinos worked hard, spoke English and took orders. Tita and Emmet had seen the workers coming home with the Look — leather jackets, Ray-Bans and enough gold around their necks to turn their skin yellow with a case of Saudi “hepa.” But most of the jobs were controlled by recruiting agencies, which charged placement fees of a month’s salary or more. Only the privileged among the poor could leave.

In the spring of 1980, Tita’s brother Fortz took a loan from his father to try his luck in Riyadh. He had just landed when Emmet’s boss asked if he wanted to do the same pool-cleaning work in Dhahran. “Yes, yes, yes,” Emmet said. The firm that managed the stadium had a contract there, so there were no recruiters’ fees. Tita’s brother Fering came the following year, and soon after, her brother Servando. Of the 11 siblings in her generation, nine either became overseas workers or married one.

“First timers” have it rough. Emmet shared a comfortable company apartment and a cook with three other Filipinos, but the loneliness was worse than anything he had known. Outside of work, there was nothing to do. Alcohol and churches were banned. Looking the wrong way at a Saudi woman was an invitation to arrest. (That is one theory behind the Ray-Bans.) Emmet paced Dhahran malls and stared at Dhahran skies, fantasizing that the planes overhead had come to take him home.

Tita’s loneliness was costly, too, but she had Emmet’s earnings. With a monthly salary of $500, he made as much in two years in Dhahran as he did in two decades in Manila, and he sent two-thirds of it home. Tita bought better food, and she bought Rowena medicine. She bought each child a second school uniform, so she would not have to wash every night. She bought an electric fan and a television — her habit of watching through a neighbor’s window was a source of alleyway discord. Emmet, who talked to the family on cassette tapes, surprised Tita by sending one with a $100 bill inside.

When Emmet got home in 1982, he gave himself a party, patched the walls and replaced the leaky roof. Then he signed another two-year contract. After his second tour, he replaced the wooden walls with cement block and added an upstairs. After his third contract, he paid the government $2,000 and got title to the land. Though neither Tita nor Emmet finished high school, all five children started college; four got degrees. Emmet, overseas paying the bills, missed every graduation. It takes a lot to move him to anger, but even now he gets furious when someone says that overseas workers leave their children to grow up without love. “You cannot look at each other and say it’s love if your stomach is empty,” he said. “I sacrificed!”

I first met Tita and the kids in 1987, as Emmet was finishing his third contract. I had a fellowship from the Henry Luce Foundation to study urban poverty; a Leveriza nun, Sister Christine Tan, introduced us, and Tita agreed to let me move in. With Cory Aquino finishing her first year, the country was in transition, and Tita was, too. She was no longer quite so talkless. I awoke in the mornings to the blare of Tagalog news radio and once found her studying an English newspaper with a dual-language dictionary. “What’s imperialism?” she asked. When Congress wanted a witness for a hearing on urban poverty, Sister Christine had Tita testify. Tita told me she had been asking God, “Why are so many Filipinos poor?” When I asked if God had answered, she laughed. “Not yet,” she said.

Much of the credit belonged to Sister Christine, who had organized a network of prayer groups and cooperative stores and groomed Tita as a lieutenant. Tita bought and distributed 2,000 eggs a week for the group’s co-op stores, placing them under a fluorescent light at night to keep the rats away. The unpaid work, undertaken in the spirit of community service, brought Tita new confidence. But so perhaps did the modest comforts made possible by Emmet’s wages. By now she had a toilet.

Her oldest two children spent less time mulling the meaning of life — Rowena, still poised between sickness and health, was addicted to celebrity gossip — and her two youngest were little boys. But Rosalie, the middle child, was on a quest. At 16, she was ambitious, sometimes brooding, beautiful and devout; while her sister squealed about movie stars, Rosalie wrote Tagalog plays about class conflict. One depicted Imelda Marcos conniving to raze Leveriza and put up a discothèque.

Emmet returned a few months into my off-and-on stay. He had missed half the life of his 11-year-old, Roldan, and nearly the whole life of the 7-year-old, Boyet. He wanted to stay. With jobs scarce, frustration rose all around. Emmet scolded Tita for running up the light bill with her stewardship of the eggs. Tita got angry when she heard Emmet urge their oldest child, Rolando, to join the U.S. Navy, and furious when she caught him encouraging Rosalie to go abroad. Emmet wanted her to be an O.F.W.; Tita wanted her to be a nun. Though Emmet found a temporary job, he was back in Riyadh within a year.

One day he opened the door to find his son Rolando on the steps. He had quit tech school to try his luck as a driver for a Saudi family. His luck proved mediocre. The salary was low, his hours were long and his secret courtship of a Filipina maid could have landed him in jail. He quit after his second contract. By then, Rosalie had finished nursing school in Manila, a milestone for the family. She had set her sights on a job in the United States, but narrowly failed the licensing exam. Four years after graduation, she still earned $100 a month. Saudi hospitals paid nearly four times as much. After borrowing the recruiters’ fee from an aunt, Rosalie was Jeddah bound.

No one fully understood that a baton was being passed. With the kids grown, Tita soon rented out the house in Leveriza and started building another on her share of the family farm. At 55, Emmet had given his prime years, nearly 20 of them, to a succession of Arabian pools. Rosalie, renewing her contract, insisted he go home. The responsibility of supporting the family was hers.

As an Islamic state that bans socializing between unmarried women and men, Saudi Arabia held out few hopes for marriage or kids. Rosalie approached her 30th birthday resigned to a dutiful life alone. She celebrated at a Jeddah restaurant with Filipino friends; one of them, knowing they had a private room, disregarded the gender rules by bringing along her nephew, a construction engineer. The nephew, Christopher Villanueva, took Rosalie for an after-dinner walk, trailing her by a few paces in case the religious police happened by. “I was trembling!” Rosalie said. With both of them living in guarded single-sex dorms, their 18-month courtship occurred largely by cellphone. When they flew home in 2002 to marry, they had never been alone.

In the Philippines the following year to deliver her first baby, Rosalie saw an ad seeking nurses in Abu Dhabi. At $1,100 a month, the job paid twice what she made in Jeddah, and Abu Dhabi had no religious police. She aced the test and caught another plane to the Middle East, this time as a mother. Christine — “Tin-Tin” — was 7 months old when Rosalie tore herself away. The baby stayed on the farm and soon called her Aunt Rowena “Mama.” When a second daughter, Precious Lara, followed, she considered Rowena her mama, too. The girls cried when Rosalie held them on visits, filling her with worry and regret.

Overseas prosperity is a gift and an obligation. “Everyone needs help, and you cannot say no,” said Rosalie, who seems not to mind. She paid to complete her parents’ new house and sends them $400 a month. She sent money for her cousins’ school supplies and helped her uncle buy a cow. She lent hundreds of dollars to godparents, knowing she would never be repaid. Migration operates like compound interest, building upon itself. Capitalizing on permissive visa laws, Rosalie has now brought a cousin and three siblings to Abu Dhabi. Rowena will soon start a secretarial job, and Roldan and Boyet are working with computers. Rosalie has also gotten Tin-Tin back, though not without some continuing distress: the girl, now 4, still treats Rowena like her real mom.

Already the family benefactor, Rosalie recently got a big promotion. As a charge nurse at the Al Rahba Hospital, she now earns $2,000 a month — 20 times what she earned a decade ago when she left the Philippines. Plus she has free health care and housing. Nonetheless, she is determined to stamp one more visa on the passport page. After a decade of trying, she has passed the American nursing exam and will soon retake the English test, which she narrowly failed. “The U.S. is the ultimate,” she said. “If you make it to the U.S., there is no place else to go.”

Once upon a time — say five years ago — remittances were considered small potatoes, and possibly rotten ones. Experts saw them as minor amounts, “wasted” on consumption, and to the extent they came from professionals, as reminders of brain drain. That began to change early this decade, when research by the Inter-American Development Bank (commissioned by a remittance enthusiast named Don Terry) showed the amounts in Latin America were three or four times higher than supposed. That work got people talking, but interest surged in 2003 when Dilip Ratha of the World Bank showed the eye-popping sums extended across the globe. Migration has been a prominent development topic ever since. Of the $300 billion that migrants sent home last year, about two-thirds came through formal channels like banks, while the rest is thought to have traveled informally, in pockets or cassette tapes. By contrast, the world spent $104 billion on foreign aid. While the doubling of formal remittances in the past five years partly reflects improved counting, Dilip Ratha argues that most of the gain is real. There are more migrants; their earnings are growing; and plunging transaction fees encourage them to send more money home.

The Philippines, which received $15 billion in formal remittances in 2006, ranked fourth among developing countries behind India ($25 billion), China ($24 billion) and Mexico ($24 billion) — all of which are much larger. In no other sizable country do remittances loom as large as a share of the economy. Remittances make up 3 percent of the G.D.P. in Mexico but 14 percent in the Philippines. In 22 countries, remittances exceed a tenth of the G.D.P., including Moldova (32 percent), Haiti (23 percent) and Lebanon (22 percent).

Despite fears that the money goes to waste, a growing literature shows positive effects. Remittances cut the poverty rate by 11 percent in Uganda and 6 percent in Bangladesh, according to studies cited by the World Bank, and raised education levels in El Salvador and the Philippines. Being private, the money is less susceptible to corruption than foreign aid; it is also better aimed at the needy and “countercyclical” — it rises in response to slumps and natural disasters. By increasing reserves of foreign exchange, remittances reduce government borrowing costs, saving the Philippines about half a billion dollars in interest each year. While 80 percent of the money sent to Latin America is spent on consumption, that leaves nearly $12 billion for investment. And consumption among the poor is hardly a bad thing.

The downside is the risk of dependency, among individuals waiting for a check or for rulers (like Marcos) who use the money to avoid economic reforms. The cash could have a stultifying effect, like the “curse” of too much oil. No country has escaped poverty with remittances alone. “Remittances can’t solve structural problems,” said Kathleen Newland of the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington research group. “Remittances can’t compensate for corrupt governments, nepotism, incompetence or communal conflict. People have finally figured out that remittances are important, but they haven’t figured out what to do about it.”

Drawing boards are filled with schemes to leverage the money for development, in ways large and small. A small Manila nonprofit group, the Economic Resource Center for Overseas Filipinos, has a plan to get overseas workers to buy cows; a dairy farm in the Philippines would raise them, splitting the profits and creating jobs. More grandly, commercial banks in Turkey and Brazil have used the expected flow of future remittances as a form of collateral to issue billions in corporate bonds. This lowers the banks’ borrowing costs and increases the amounts they can lend, making it easier, in theory at least, for businesses to borrow and expand.

A goal atop everyone’s list is getting more families “banked.” Opening an account (as opposed to just wiring money) lets migrants establish credit histories for future mortgages or business loans. The deposits expand capital pools. And bank accounts boost savings rates. Some banks turn migrant deposits into tiny loans to village entrepreneurs, linking remittances to the popular realm of microfinance.

Migrants contribute to development in ways that go beyond remittances. Many countries tap their diasporas for philanthropy. Affluent migrants make investments back home. And the increasingly circular nature of migration means that some migrants return with knowledge and connections. This is a countertrend to brain drain — “brain gain” — with Taiwan the most obvious case. The Hsinchu Science-Based Industrial Park, a government-subsidized Silicon Valley, has lured home thousands of skilled Taiwanese with research and investment opportunities. The key is having something to lure them to; brain gain has not come to, say, Malawi.

Casting migration as the answer to global poverty has some people alarmed. It risks obscuring the personal price that migrants and their families pay. It could be used to gloss over, or even justify, the exploitation of workers. And it could offer rich countries an excuse for cutting foreign aid and other development efforts. “This is a new version of trickledown theory,” warned Stephen Castles of Oxford University at a recent conference in Mexico City. “It wants to make the poor pay for development.” Rodolfo GarcÃa Zamora, a professor at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas in Mexico, warned the conference against remittance “fetishization.” Even in the remittance-happy Philippines, national law states that the government does not see migration as a development strategy — though it obviously does.

Certainly, soaring remittance tallies cannot measure social costs, to migrants or to those left behind. (So many Africans die at sea each year trying to reach European soil that the Straits of Gibraltar have been dubbed “the largest mass grave in Europe.”) I was with Emmet and his brother-in-law one day when they broke into a nostalgic version of “It’s So Painful, Big Brother Eddie,” a Tagalog classic from the 1980s that immortalizes every migrant’s fear:

My child wrote to me

I was shocked and I instantly cried.

“Father come home, make it fast

Mother has another man

She’s cheating on you, father. . . .”

But what’s painful, I’m wondering

Why our two children are now three?

Among the biggest worries, in the Philippines and beyond, are the “left behind” kids, who are alternately portrayed as dangerous hoodlums and consumerist brats. Some people fear that their gadgets and clothes, sent from guilty parents abroad, corrupt village values. A U.N. envoy, examining Filipino migration, had a different concern: “Reportedly children of O.F.W.’s are more likely to become involved in delinquency or early marriage.” (Note “reportedly.”) One episode of “Because You Left,” the television show, depicts an adolescent boy whose father is abroad, leaving no one to help him with his first crush. He bonds with the school bully, steals from his mother and tries to rob someone. In addition to the “left behind,” researchers speak of a more disadvantaged class — the “left out.” Lacking the money or connections to go abroad, they are marooned on the wrong shore of what is, among the poor themselves, a growing divide.

Fear about the children is inevitable (and laudable), but the modest social science that exists offers some reassurance. At least three studies have examined “left behind” families in the Philippines. All found the children of migrants doing as well as, or better than, children whose parents stayed home. The most recent, from the Scalabrini Migration Center in Manila, involved a national survey of 10-to-12-year-olds. The migrants’ kids did better in school, had better physical health, experienced less anxiety and were more likely to attend church. “For now, the children are fine,” it concluded. Joseph Chamie, editor of The International Migration Review, an academic journal, calls the finding typical. “There’s not much scientific evidence that children have developmental difficulties when a parent migrates,” he said.

One theory is that remittances compensate for the missing parent’s care. The study found migrants’ kids taller and heavier than their counterparts, suggesting higher caloric intake, and much more likely to attend private school. The extended family can also act as a compensating force. And so can modern technology in an age of cellphones and Webcams. There is no doubt that migration has costs. “We don’t have a focus group without people crying,” said the Scalabrini researcher, Maruja Asis. The point is that not migrating has costs, too — the cost of wrenching poverty.

The Philippines, more than most places, claims to be skilled in managing these costs. As the rare bureaucracy devoted to migrant care, the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration draws admirers from across the globe. Any agency pledged to tame a force as brutal as labor migration is bound to have its failures. O.W.W.A. has 300 employees to watch over 3.6 million workers. The general Filipino view is that the agency does a serviceable job during crises abroad (it evacuated 30,000 workers from Kuwait during the first gulf war), while playing politics at home — investing funds in cronies’ businesses and helping politicians get out the vote.

But there is an especially sordid chapter of migrant history that this forgiving account omits, the shipment of bar girls to Japan. Spotting a growth market a decade ago, Philippine recruiters marched armies of young Filipinas through short courses in song and dance, then sent them off to Japanese clubs, with the Philippine government certifying them as “overseas performing artists.” Club owners typically grabbed their passports and told them to do what it took to keep customers drinking; what it took was a mix of tableside affection, off-duty dating and outright prostitution. As both governments lent a hand, Filipinas in skimpy clothes became an export commodity. Their numbers rose from 17,000 in 1996 to more than 70,000 in 2004, as remittances from Japan hit more than $350 million.

Sex work is often a byproduct of extreme poverty. “A man is on top of me,” writes Corazon Amaya-Cañete, a Filipina poet in Hong Kong, in the voice of a woman who distracts herself by resurrecting a childhood habit of counting sheep.

In exchange for this is money for Mother’s

medicine

Building the house and

Buying food for my six siblings

Clothes, shoes, books and tuition for school . . .

Seventy-seven white sheep!

Seventy-seven white sheep!

The Tagalog wordplay emphasizes the cruelty of her fate: she starts life as a girl counting tupa and awakens to find herself a puta. “Oh! I am prostitute!” she screams. (The poem, “Seventy-Seven White Sheep,” was published in a Webzine of Filipino diaspora writings, Our Own Voice.)

It was not the Philippines but Japan that finally cleaned things up. It acted only after the U.S. State Department placed it on a 2004 watch list of countries lax toward human trafficking. The embarrassed Japanese now demand two years of performing experience for an entertainer’s visa, which has cut the flow of Filipina bodies by about 95 percent. Remarkably, it did so over the objection of the Philippine government, which sent a protest delegation to Tokyo.

Or perhaps it is less remarkable than it seems. A handful of advocates condemned the flesh trade, but most Filipinos see it as a consensual, if regrettable, economic exchange, and inevitable in a country where nearly half the population lives on less than $2 a day. Gina gawa ko dahil para sa familya ko goes the Tagalog saying. “I do this for the sake of my family.”

I asked Nito Roque, the country’s chief migrant protector, how to square the sex trade with the government’s pledge (in Act 8042) to protect workers’ “dignity and fundamental human rights.” His answer says something about the limits of migrant protection, in the Philippines and beyond. “The contract does not say anything about prostitution — that is a private matter between the employer and the employee,” he said. “Nobody forces anybody to go abroad. It’s the applicant who comes forward and applies for the job.

“Do they know what they’re getting into? I think so.”

About 30 miles south of Manila, just outside the town of Silang, a dirt road ends at a residential compound carved from a small coffee farm. For decades it held nothing but the thatched hut where Tita and her 10 siblings were raised. Now a dozen cement blockhouses are clustered in a U, some little more than shells and others, like Tita and Emmet’s pink cottage, boasting faux marble tile and lace curtains. One look at each home yields a fair guess of how long the owner worked abroad. Nine families in the compound sent workers overseas, and collectively those workers stayed for 131 years (and counting). A walk across the compound cuts through a century of rewards and regrets.

Tita’s brother Fering is thankful that he returned from Saudi Arabia in time to see his children’s first days of school. Another brother, Fortz, is one of two men in the family (by some counts, three) whose extramarital affairs overseas produced kids. He left for Saudi Arabia with a daughter named Sheryl and returned with another named Sheralyn. Conscripted as a stand-in mom, Tita raised the girl for 10 years — resentfully at first, because of the cost — and wept when her real mother took her away. “She is like having another child,” she said.

Tita’s sister Peachy learned that her husband had a girlfriend — and a son — when she received a package meant for them. The first time I asked her whether the time apart had strained their marriage, she politely lied. “No — we’re loving each other for ever and ever!” she said. The following day she sought me out with a more candid account. Peachy is a large, cheerful woman, who seems as if nothing could daunt her. “I almost died,” she said. “I couldn’t lose my husband to someone else. That was the saddest moment of my life.”

Peachy’s sister Patricia thought all was well until a stranger called two years ago and said her husband was having an affair with his wife. “Your husband and his mistress,” the man wrote on the photograph that followed. When Patricia called her husband in Saudi Arabia, he denied all and then stopped taking her calls. He sends little money, and she suspects he has a new child. Their son Jonvic, a dimpled 9-year-old, renders judgments of his father with innocent cheer. “What he did to us was worse than if he died, because he violated the Ten Commandments of God,” he said.

It was not infidelity that moved another relative to tears but fidelity at any cost. We were breezing through the family photo album when she pointed at a picture from Saudi Arabia that showed her husband at an evangelical church. Church? That is a ticket to deportation or worse. Alarmed that her slip might place him in greater dangers, she started to sob. “I can’t stop him — that’s where he found his happiness,” she said. When I reached him, he encouraged me to mention his preaching, saying it was his way of thanking God for the chance to work abroad. “I promised the Lord I’ll share the Gospel under any circumstance,” he said.

The nine families of overseas workers raised 35 kids, some of whom scarcely saw their fathers. Their combined stories could fill a whole season of “Because You Left.” One became pregnant at 17 and is now a single mother. Another became addicted to video games and dropped out of school. Yet another started drinking after his father disappeared. One of Tita’s sisters sold a house and a cow to place her son in a Taiwan factory. The son squandered his parents’ life savings within a few months, and his drinking and gambling got him expelled from the country.

By any measure, the price was high, yet there it stands — a semicircle of blockhouses where there once was a mere thatched hut. Bookshelves sag with encyclopedia sets. More diplomas appear each year on freshly plastered walls. There are bunk beds and Bugs Bunny sheets, cellphones, stereos and big televisions. Having nearly lost her marriage to labor migration, Peachy is scarcely heedless of its social costs. “A good provider is someone who leaves,” she said, without ambivalence.

One irritant of life in the compound has been the shared well, which dries up and causes contentious waits. Three of the families have drilled wells of their own, with electric pumps. One belongs to Peachy, a gift from her daughter, Ariane, who used her father’s overseas earnings to get a degree in hotel management and earns $1,000 a month as a maid on a cruise ship.

Another tank belongs to Tita and Emmet, whose cottage is the compound’s jewel. It has a patio, a beamed ceiling, a tiled sala floor, two kitchens and two toilets that flush. It was built by Rosalie and is a monument to the tenacious child who wrote plays about the rich exploiting the poor and willed her way into the nascent middle class. Although she is thousands of miles away in Abu Dhabi, she hovers over the compound; no household there is heedless of her example or generosity.

The house is nicer than any that Tita and Emmet have known but quieter too, with four of the couple’s five children a continent away. “I am sad,” Tita said, “because they’re in a far place.” She is often weak with ulcers, and Emmet’s hearing has started to fade. They had a chance to sell the fixed-up house in Leveriza for a princely sum, $16,000, but unwilling to part with the place where their children were raised, they rent it to relatives. Restless without work, Emmet is especially susceptible to nostalgia for the bad old days. “I was happier then because I was with my children,” he said.

Going abroad is difficult, but so is coming home. Since Emmet returned for good, the kids have noticed less tenderness between their parents and more quarreling. They each grew accustomed to being the boss. One reason Rosalie left her second daughter, Precious Lara, in the Philippines is that she thinks her parents need a child to love. Tita and Emmet sleep beneath a malaria net with the 18-month-old beside them, and Rosalie often calls home two or three times a day. She and her husband have an infant son, Dominique Edward, in Abu Dhabi, whom her parents have never seen. Armed with her first cellphone at 60, Tita has sent so many text messages that she has worn the numbers off the keys. Yawning one night, she laughed and said of herself, “Low batt!”

Off the sala is a guest bedroom with a large framed photograph of Rosalie, taken on her wedding day. The woman in that picture shows no trace of a birthright of poverty. She turns to the camera wearing an enormous gown and a confident face. Two generations of labor migration have given her more education, more money and more power and prestige than her mother could have dreamed of on her own wedding day. Precious Lara rarely plays in that room and hardly knows the face, much less the sacrifices her mother has made for the blessings of a migrant’s wage.

Jason DeParle, a senior writer for The Times, last wrote for the magazine about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Next Article in Magazine (1 of 14) »